The Massachusetts Water Environment Association (MAWEA), working together with the North East Biosolids & Residuals Association (NEBRA) and the New England Water Environment Association (NEWEA), has started a conversation with state regulators about the best ways to manage the 2,475 wet tons of wastewater sludges that need to be managed every day in Massachusetts – that’s the equivalent of 88 tanker trucks bringing biosolids somewhere every day – in light of concerns about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

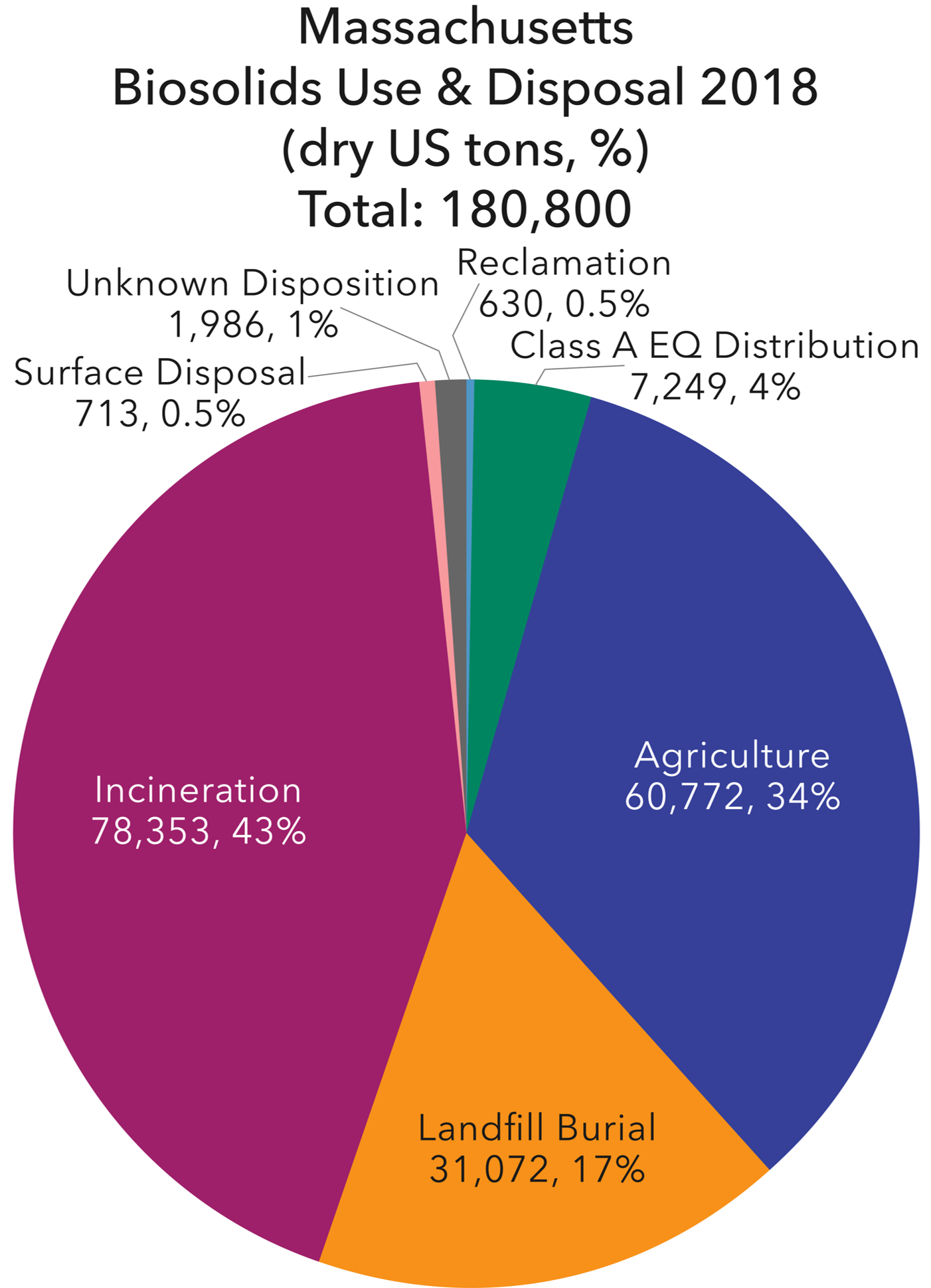

According to Massachusetts — National Biosolids Data Project data collected by NEIWPCC in collaboration with NEBRA’s nation-wide study, Massachusetts disposes/uses more biosolids by far than the other Northeast states, with the exception of New York. See Figure 1: Northeast Biosolids End-Use and Disposal.

Figure 1: Biosolids End Use and Disposal in the Northeast (credit: NEBRA)

Currently, the ultimate end uses of biosolids generated in the Commonwealth are pretty evenly distributed between incineration, landfilling and recycling. However, the state is vulnerable to upsets due to high reliance on out of state outlets. According to MAWEA’s Mickey Nowak, who went through each and every annual biosolids report entry into EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online | US EPA database, 70% of Massachusetts biosolids are heading out of state. “This is somewhat of a moral issue and we should not be relying on other states to take our biosolids,” he said. Nowak fears major impacts on water resource recovery facilities (WRRF)’s options for managing these materials which could result in operational and water quality impacts, not to mention major cost increases.

On November 15th, MAWEA, NEBRA and NEWEA wrote to Martin Suuberg, the outgoing commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), requesting a meeting to discuss big picture plans for managing the state’s biosolids.

In response to the letter, the MassDEP reached out to MAWEA and set up a virtual meeting with key members from MAWEA, NEBRA, and NEWEA. The three organizations have a lot of members in common and they are all concerned about the rapidly rising costs and declining outlets for the biosolids generated by the 7 million people living in Massachusetts, including the nearly 30% of them relying on septic systems. There was a broad collation of NEBRA members participating in the meeting, including wastewater utilities, biosolids managers (including recyclers and incinerator and landfill operators), septage hauler and consultants.

At the meeting held on January 3rd, MAWEA and the other stakeholders asked MassDEP to resume the stakeholder process for PFAS in residuals that started over 2 years ago (see PFAS in Residuals | Mass.gov) and consider a master plan for biosolids management. These biosolids stakeholders cannot afford any more delays or confusion; solids management contracts are expiring and capital investment plans have been on ice. MassDEP reported on the PFAS in Residuals technical subgroup of researchers which has met 3 times since 2020, helping to inform the MassDEP’s modeling work. In addition, Massachusetts has been collecting data from Approval of Suitability (AOS) permit holders for several years now and expressed concerns with data indicating some of the residuals concentrations exceed the levels set forth in the Massachusetts Contingency Plan (see Final PFAS-Related Revisions to the MCP (2019) | Mass.gov) for site/soil clean up.

MassDEP staff expressed major concerns about biosolids/residuals land application based on their leaching models using the current state drinking water/groundwater standards as the end point. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s recently announced lifetime Health Advisory Limits (HALs) would only increase those concerns as the HALs will be factored into the EPA’s calculus for setting Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs). However, the EPA will consider things like analytical limitations, a lack of available treatment technologies, as well as the costs of treatment versus the public health benefits of setting very low MCLs. The MassDEP plans to revisit it PFAS drinking water MCLs in 2023.

The MassDEP’s PFAS leaching model does not take into account research/data showing decreasing levels of PFAS in biosolids as sources are removed from wastewater collection systems. MassDEP admitted it’s tough to predict the future at this time with so many variables changing but WRRFs should expect lower targets for PFAS in biosolids in the future, despite decreasing sources and concentrations. MAWEA, NEBRA and NEWEA plan to continue informal discussions with MassDEP. Formal stakeholders meetings will resume this year, according to MassDEP.